“Why’s your mum in hospital?”

“She’s sick.”

“What with?”

“Lymphangioleiomyomatosis.”

“What?”

“LAM.. It’s a lung disease.”

“Oh, never heard of it.”

Most people haven’t. But that never stopped me from starting on an extended and detailed definition of the disease, including prognosis and history, before the other person in the conversation would awkwardly change topics. I was always so angry that no one knew what this disease was. It was killing my mum. Everyone should know about it.

In 1994 my mother was playing competition beach volleyball. She was married with two young children, five and three (me). During a game she noticed her breathing was wrong. Over time it got worse. She began to cough up blood. Haemoptysis. Knowing something was wrong she went straight to the doctor. It was nothing. It was in her head. She was imagining things. For six months she was told that she was fine but she knew she wasn’t.

Eventually a lung biopsy proved her correct and she became one of the first Australians diagnosed with lymphangioleiomyomatosis, commonly known as LAM. An irreversible lung disease, LAM causes cysts to grow and replicate in the lungs, causing shortness of breath and eventually, death.

I don’t remember the actual moment when my mum told me she was dying. I don’t recall her telling me about LAM and the five-year sentence she had been given. I don’t remember struggling to understand or accepting that my Mum wouldn’t see me turn ten. It was always just a fact to me: my Mum was sick. Just like B comes after A in the alphabet, it’s something that I have known for most of my life.

After her diagnosis my Mum was given a medication called Depo Provera. With the disease being so new and misunderstood this was the only option given. The side effects included severe mood swings and didn’t actually help with Mum’s breathing at all. She was told that having another child would kill her but she was OK with that because she had two children whom she loved more than anything.

The diagnosis was too little too late because she was now a single mother with a large decision to make. She didn’t want to spend her last years with her children as a moody mother. She stopped medication and moved to the Gold Coast for support from her parents as she waited for the disease to take her.

She moved it to the back of her mind and tried to stay positive, until she remarried and until she became pregnant again. She found a lung specialist who told her the pregnancy should be fine. But due to separate complications… it wasn’t.

After losing the baby, she made a decision. She would fight the disease long enough for her children, for me, to decide where to live when – not if – the worst would happen. She had already beaten the five-year mark that had been looming. With medical advances and new research into the disease she finally had new options for medication.

It was during this time that I began to understand the reality of the disease. It developed from a long and scary sounding word into the reason my mum was always in hospital.

Soon I was receiving phone calls from my mum who had simply gone to the doctors for a check-up and been rushed to the hospital. I took on the role of collecting her car and bringing her food and coffee. I visited her daily and watched as a woman, who didn’t even look sick, cling to an oxygen mask for survival.

She wasn’t at the point where a lung transplant would be necessary so it became a game of waiting and hoping and using Doxycycline, another trial medication with no guarantees.

It was an almost weekly occurrence that I’d bring a tray to her bed, including a Milo, pain medication and a flower.

Eventually she was prescribed Sirolimus. It wasn’t easy; she was required to go through a long application from the government to seek approval.

Now, for the first time I can remember, my mother can spend an hour walking along the beach. She can stay awake after eight o’clock in the evening. She can spend a few hours shopping with me, if fact she can spend an entire day out with me if she wants to.

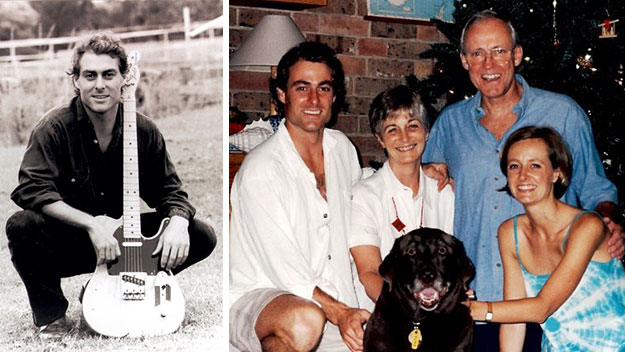

Left: Gai on oxygen in hospital. Right: Recent photo of Gai looking better than ever.

She has reached out to old friends and she’s happy. She doesn’t go to sleep every night wondering if that will be the night that she takes her last breath.

She isn’t healed but she is finally alive again because her life had been on hold for 20 years since she was diagnosed in 1994.

Somthing she was never supposed to do: Gai enjoying the sun on her paddle board on the Gold Coast.

The bottom line is LAM is devastating, LAM is aggressive and LAM has no cure… yet. I want to be there for my Mum like she has been for me and if there’s anything she has taught me, it is never to give up. My mother is a living example of the power of positive thinking.

This reader’s story was shared in conjunction with Rare Disease day on February 28.

What is LAM?

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a cystic lung disease. It’s rare – LAM Australia Research Alliance lists only 100 women living with LAM in Australia. Worldwide an estimated eight women in a million have LAM.

Is Lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) genetic?

Some of those women inherited LAM from their mothers along with tuberous sclerosis. The others were diagnosed with LAM after a random genetic mutation caused a sudden extreme incident – a collapsed lung, a ruptured renal cyst, or a build-up of fluid in the chest cavity.

Is LAM easy to detect?

Diagnosis is often delayed because not all doctors know about LAM and the symptoms resemble other conditions like asthma and emphysema.

What are LAM’s symptoms?

Breathlessness is something all women living with LAM have in common. That’s because if left untreated, LAM gradually destroys the lining of the lungs.

Is there any hope for a cure for LAM?

Thankfully, a US-led drug trial showed that Sirolimus slowed the destructive process in some women. That’s the drug that has raised the hopes and improved the lives of women like Gai Golder.

For those women who don’t respond to Sirolimus or similar drugs, the big hope is that researchers will develop targeted treatments to stop LAM destroying their lungs.

LAM Australia Research Alliance is a not-for-profit founded to raise funds for LAM research, raise awareness of LAM, and support women living with LAM. For more about LAM or to donate to research visit LAMaustralia.org.au

If you have an idea for a reader’s story please contact us via our Facebook and if it’s something we think we can share we will get in touch.